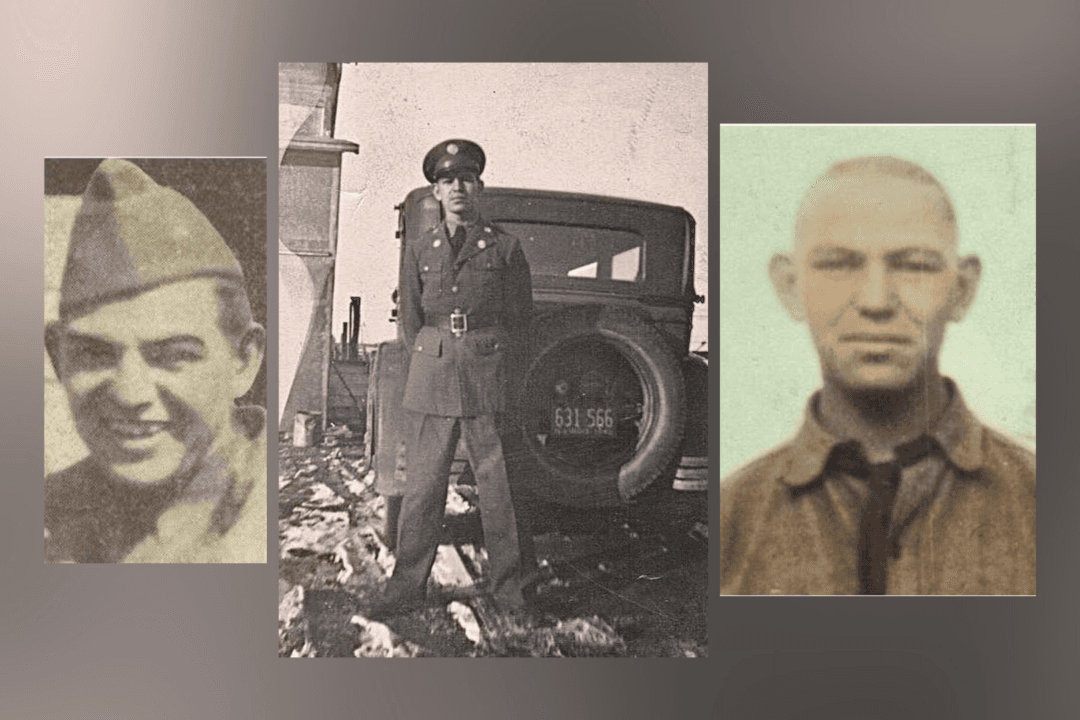

It has been a long journey home for U.S. Army Private First Class Harry Jerele.

He was 24 when he enrolled in the Illinois National Guard (ILNG) to serve his country during World War II. He paid the ultimate sacrifice at the young age of 26 in one of the worst prisoner of war camps.

Now more than 80 years later, he will finally be laid to rest in America.

The Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA) recently announced Mr. Jerele’s remains were identified, and he will be buried in Abraham Lincoln National Cemetery in Elwood, Illinois, with full military honors.

His funeral is scheduled for Oct. 4.

“The story of the 192nd Tank Battalion is both extraordinarily heroic and horrific. More than 80 years later we continue to draw inspiration from Private First Class Harry Jerele and the rest of the 192nd,” said Maj. Gen. Rich Neely, the adjutant general of Illinois and commander of the Illinois National Guard, in a statement included in the announcement.

Family Remembers Soldier

An ILNG spokeswoman told The Epoch Times, “there are still members of the ILNG unaccounted for from World War II.” While she did not have the total number, she noted there are approximately five from Mr. Jerele’s unit still unaccounted for.“This is a miracle,” Rosemary Dillon, Mr. Jerele’s niece, said in the announcement. “We’ve been trying for about 10 years to positively identify his remains. It’s been a long time coming. What a joyous occasion it will be when he is finally laid to rest in his home country.”

Ms. Dillon said she remembers her uncle was a very quiet man.

“He liked to sing and play guitar,” she said. “He was an unassuming man, but he had great friends who joined up with him.”

Ms. Dillon said the one thing that makes his homecoming bittersweet is that Mr. Jerele’s sister and mother are no longer alive to be there to welcome him.

“I only wish my mother and grandmother were here to witness his homecoming,” she said.

Mr. Jerele was part of the ILNG Company B, 192nd Tank Battalion, that was activated for service and arrived in the Philippines days before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

He was among the first soldiers in the U.S. Army to engage the enemy in tank warfare in WWII. His unit was forced to surrender several months later. These soldiers were the longest held POWs in the war, and many were part of the Bataan Death March and the Japanese POW Hell Ships, the ILNG said.

During the Bataan Death March, captured soldiers were forced to march through the Philippines, a route that was 65 miles long.

The National WWII Museum reports that the march was “an absolute tragedy. The prisoners of war were forced to march through tropical conditions, enduring heat, humidity, and rain without adequate medical care. They suffered from starvation, having to sleep in the harsh conditions of the Philippines. The prisoners unable to make it through the march were beaten, killed, and sometimes beheaded.”

Final Days

Mr. Jerele died Dec. 28, 1942, three years before the camp was liberated in early 1945. He was one of 2,500 Americans who died in that POW camp. He was buried in Common Grave 804 at the local Cabanatuan Camp Cemetery along with other deceased American POWs.After the war, the American Graves Registration Service exhumed those buried at the cemetery and relocated the remains to a temporary U.S. military mausoleum. While some remains from Common Grave 804 were identified, the others were unidentifiable and buried as unknowns at the Manila American Cemetery and Memorial until 2020, when the remains were disinterred and sent to the DPAA for analysis.

The DPAA announced Mr. Jerele’s remains were identified using anthropological analysis and circumstantial evidence. Scientists from the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System used mitochondrial DNA analysis to identify his remains.

“For all of us who work here at DPAA, this is our mission, this is what we do. And we are passionate about this mission. This is something that means something to individual people,” Sean Everette, media relations chief of the DPAA, told The Epoch Times.

“What we do is important to individuals, and we are able to bring answers to some families, closure to other families. We help them fill a gap that has been in their family for 80 or more years,” he said.

An Army veteran himself, Mr. Everette said, “I’m proud to be a part of that because it is important that these people are never forgotten.”

Mr. Everette said it is the DPAA’s “almost sacred duty” to these service members, who raised their hand and took an oath to uphold the Constitution. In return, the country also promised to never leave them behind.

With the realities of war, it “may be years or decades before we can bring them home,” he said. “But we are here to fulfill that promise to bring them home and never leave them behind.”