Audiences are not drawn to Shakespeare’s characters for their “Englishness,” or Raphael’s paintings for their Italian characteristics, or Beethoven’s music for its native German qualities. Artists are great because of the way they capture the universal dimensions of being human.

We still, alas, cannot forestall it— This dreadful ailment’s heavy toll; The ‘spleen’ is what the English call it, We call it simply ‘Russian soul.’

To this day, Russian schoolchildren memorize Pushkin’s verse. That’s a stark contrast to most Westerners, who have not read him (and are not memorizing any verses, either). As far as teasing out exactly what Pushkin meant by “Russian soul,” the title character in the 1987 film “Withnail and I" put it memorably when he dismissed Russian dramas as “full of women staring out of windows, whining about ducks going to Moscow.”

The Beginnings of ‘Russian’ Music

After the Russian army thwarted Napoleon’s 1812 invasion by burning Moscow, a sense of national pride and interest in past traditions led the people of that vast nation to develop sophisticated works of art on par with their western neighbors. The most important of these early figures was Pushkin. His parallel in music was Mikhail Glinka, whose 1836 opera “A Life for the Tsar” incorporated European aspects of drama, counterpoint, and melody with unique Russian folk tunes and settings. After hearing the opera, Prince Vladimir Odoyevsky wrote, “This is the dawn of a new age in the history of the arts—the age of Russian music,” according to Stuart Campbell in his “Russians on Russian Music.”The Mighty Five

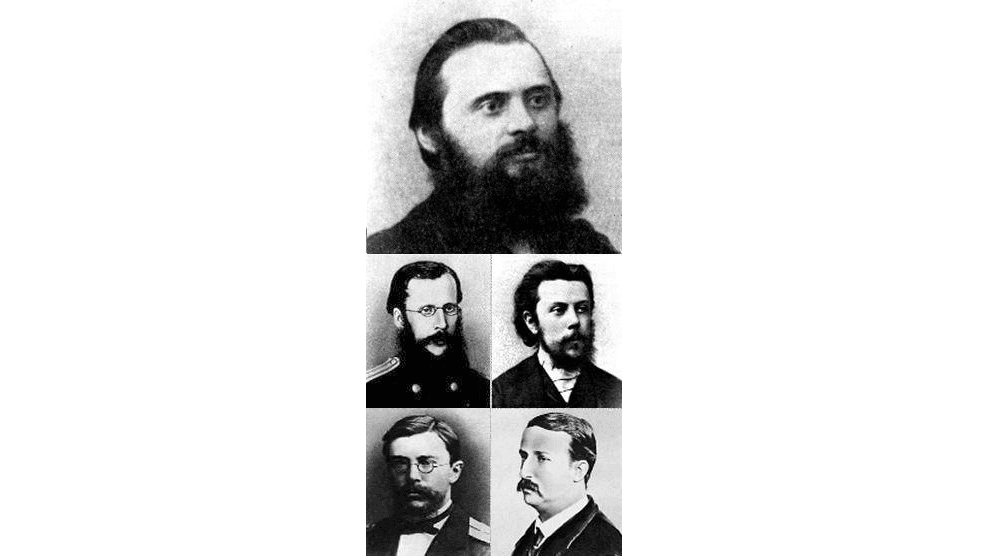

When Westerners think of distinctively “Russian” music, names that most often come to mind (after Tchaikovsky) are those in the group that has come to be known as the Mighty Five (“moguchaya kuchka”—mighty little bunch). They are Mily Balakirev, Modest Mussorgsky, Alexander Borodin, Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov, and Cesar Cui. They stood outside of the academic establishment, and, aside from their leader Balakirev, learned music by studying on their own.

Cui was a prolific opera composer but is more remembered today for the memoir he left about the group than for his music. Balakirev (1837–1910) arranged many influential folk songs, publishing them in two collections. Borodin (1833–87), a chemist by trade, left many works unfinished that were later polished by Rimsky-Korsakov (1844–1908). The most recognizable piece among Borodin’s oeuvre is the “Polovtsian Dances” from his opera “Prince Igor.”

Night on Bald Mountain

Modest Mussorgsky (1839–81) was the greatest and most innovative of the Mighty Five. His masterpiece is the opera “Boris Gudonov,” about the tsar of the same name. In the West, though, he is best known for his symphonic tone poem, “Night on Bald Mountain.” This is largely because Walt Disney exposed Mussorgsky to millions of young children by animating it as the pinnacle of “Fantasia” (1940). Mussorgsky stamped his personality onto his work, and the music’s dark themes about a Witches’ Sabbath mirror the darkness in Mussorgsky’s own life. Of all the group, he probably came closest to matching Pushkin’s stereotype of the Russian soul.As a composer outside the establishment, Mussorgsky worked a tedious, low-paying clerical job to pay the bills, which caused him to sink into “sadness, sadness, and tears” since he felt he was wasting his musical talent. Suffering financial woes, he turned to drink and died shortly after his 42nd birthday.

After Mussorgsky’s death, Rimsky-Korsakov inherited his friend’s oeuvre. As with Borodin, he completed Mussorgsky’s unfinished pieces and made them available to the public. It was his arrangement of “Bald Mountain” that was used in “Fantasia.”

Rimsky-Korsakov later became a professor at the St. Petersburg Conservatory, the institution that the Mighty Five had originally defined themselves against. Like so many, the rebel became part of the establishment in his old age. This move, paradoxically, enshrined the Five as the founders of a Russian school of music, as Rimsky-Korsakov championed the memory and work of his old friends. This Russian school, in turn, influenced other Western composers who brought Glinka’s European borrowings full circle. Without Rimsky-Korsakov, Mussorgsky, Borodin, the others would likely still be obscure.

Contrary to the myth of the solitary artist, everyone needs a helping hand. Three cheers for friendship!