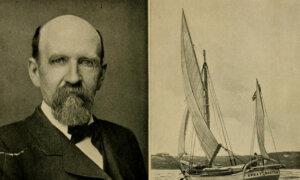

Henry Fitz Jr. was always interested in how things worked. As a locksmith journeyman, he saved his money, studied astronomy, and built his own telescopes. Soon his telescopes rivaled the finest in the world and were placed in some of the country’s most prestigious observatories.

Henry Fitz Jr. (1808–63) was born in the small town of Newburyport, Massachusetts, where the Merrimack River meets the Atlantic Ocean. The town was known for its maritime trade and shipbuilding. Henry Fitz Sr., however, was a hatter. A few years after his son’s birth, disaster struck the city.

In 1811, a fire destroyed Newburyport’s downtown. While the citizens worked to recover and rebuild, the War of 1812 broke out. Restrictions and embargoes on trade placed the town and businesses in further financial straits. The financial conditions only worsened with the Panic of 1816. By 1819, the Fitzes left Newburyport for Albany, New York, where the husband and father of three briefly plied his trade. But financial opportunity seemed more readily available south of Albany in New York City, and the family soon moved.

Career Moves

Before his 20th birthday, Fitz moved toward a more mentally and physically demanding career. He began work as a journeyman locksmith for William Day of New York. This career lasted from 1830 to 1839, and saw him travel around the country, primarily from New York City to Philadelphia; Baltimore, Maryland; and Cincinnati, and as far west (and south) as New Orleans.During this time of locksmithing and work travel, Fitz pursued an interest in astronomy. While not at work, he studied and read works on the science of celestial bodies. Toward the end of his career as a journeyman locksmith in 1838, Fitz built his first telescope. It was for his personal use, although he often invited friends to peer through it. Fitz continued studying telescopes, while at the same time, his interest was piqued by the invention of the camera and the works of Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, the French inventor of the daguerreotype process.

The invention of this process was announced at the French Academy of Sciences in Paris in August of 1839. Instead of using a photo negative, an image could be developed on a plate of copper overlaid with a thin sheet of silver. For about a decade, the daguerreotype process of photography was in high demand. In 1840, a friend of Fitz’s, Alexander Wolcott, invented the lensless daguerreotype camera. Fitz used his friend’s camera to take an image of himself. It is considered one of the first (if not the first) copper daguerreotype images created in the United States. In 2021, the daguerreotype image of Fitz was sold at auction for $300,000.

Building the Fitz Telescopes

Toward the end of the 1840s, Fitz began building telescopes in earnest. At the time, there were no American telescope manufacturers; all telescopes were typically shipped from England or Germany. The largest available in America were six-inch telescopes.During the summer of 1845, Fitz exhibited his telescope at the annual Fair of the American Institute. His invention won the gold medal prize, the first of several he won over the years. One of the fair’s attendees was Lewis Rutherfurd, a wealthy lawyer, amateur astronomer, and trustee at Columbia College (later University). Rutherfurd asked Fitz to make him a four-inch telescope, making him one of Fitz’s first customers.

Fitz soon opened his telescope business in New York City. The quality of his achromatic telescopes were on par with the finest available from Germany.

Fitz and the Observatories

Over the course of the next 15 years, Fitz continued building telescopes. According to records, his first sale to a public institution was to Erskine College in 1849. As more observatories popped up across the country and people became more interested in astronomy, Fitz’s business flourished. In 1852, he built a 12-inch telescope, which was later sent to Wellesley College. In 1856, he built a 10-inch telescope for West Point Military Academy. In 1857, he built a 12.25-inch telescope for the Detroit Observatory. In 1861, he built a 12-inch telescope for Vassar College source (the same used by Maria Mitchell, who was highlighted in “Profiles in History” on Feb. 16, 2024). Also in 1861, Fitz built a 13-inch telescope for Pittsburgh’s Allegheny Observatory.

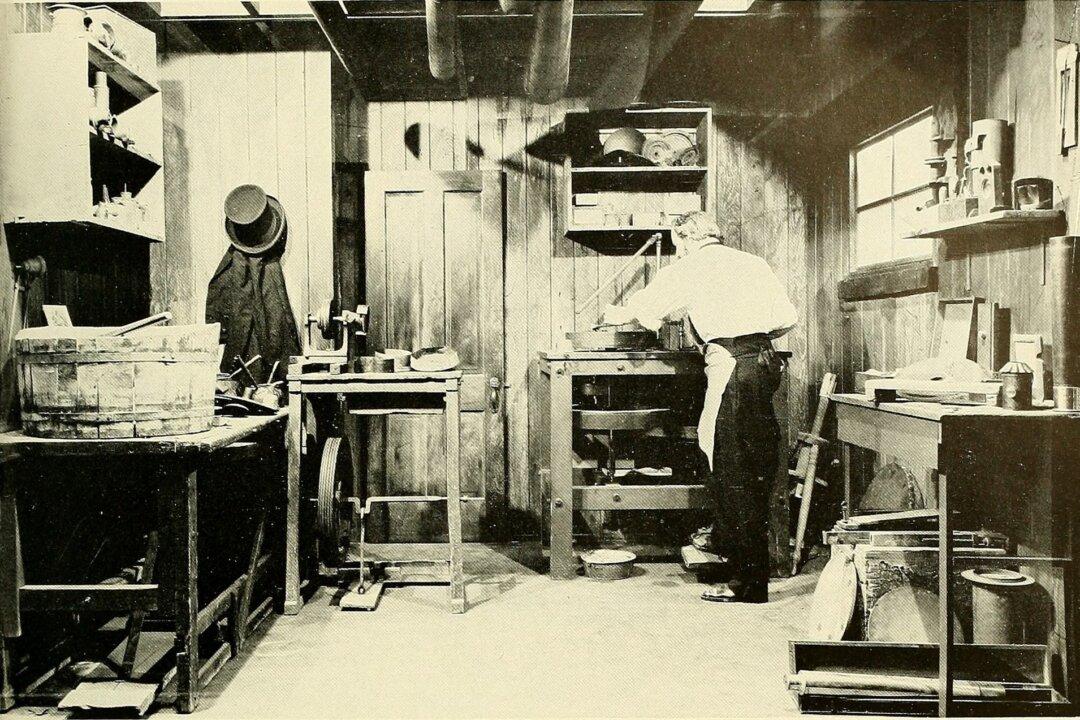

Exactly a century after the Fitz telescope was installed at the Detroit Observatory, his entire workshop was moved and reconstructed inside the Smithsonian Institution as an exhibit. The Fitz telescope at the Detroit Observatory was used to discover more than 20 asteroids, three comets, and was used to map Mars.