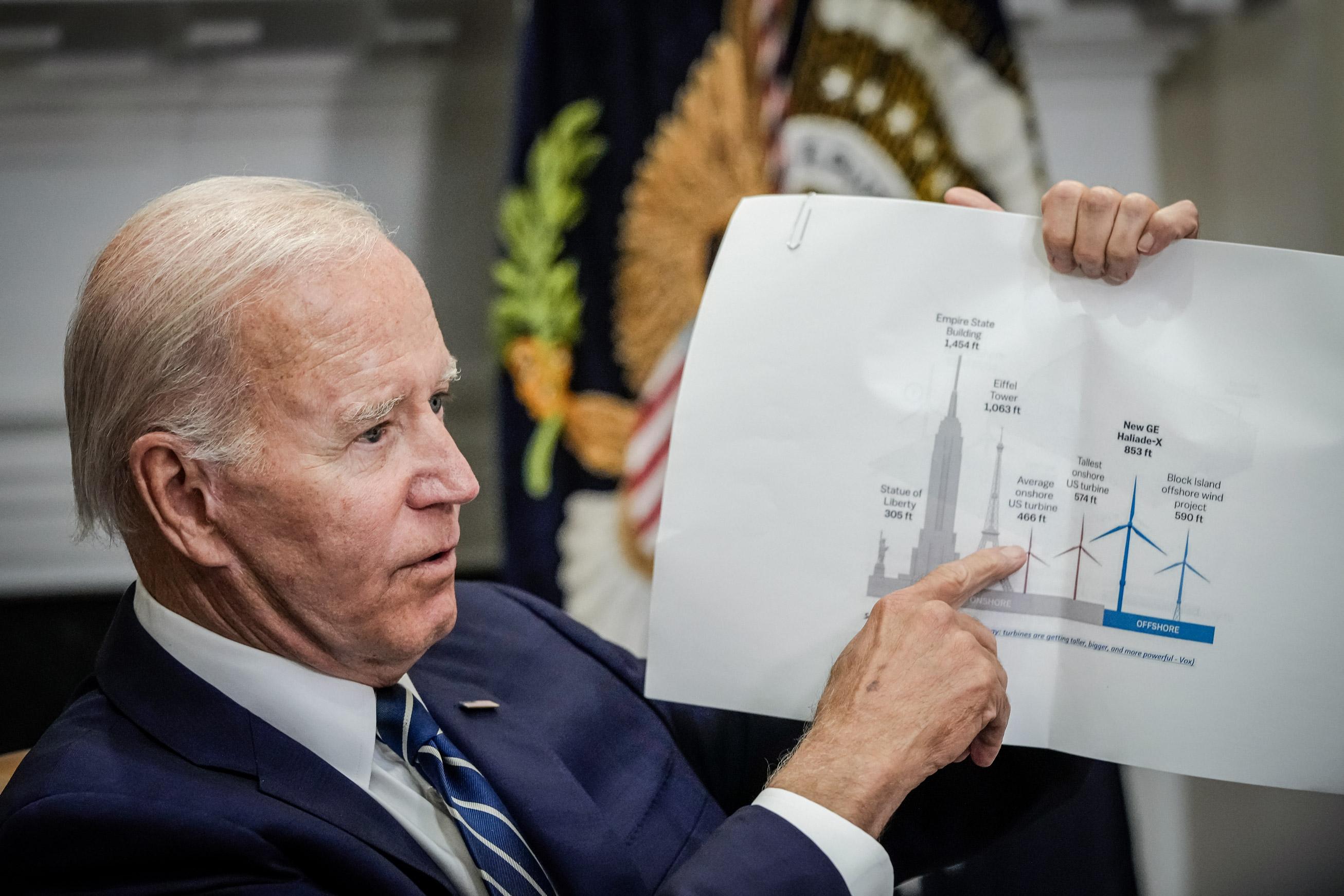

As the Biden administration expands its offshore wind projects as part of its goal to reach a carbon-free energy system, whales and other marine life may become collateral damage, according to new research.

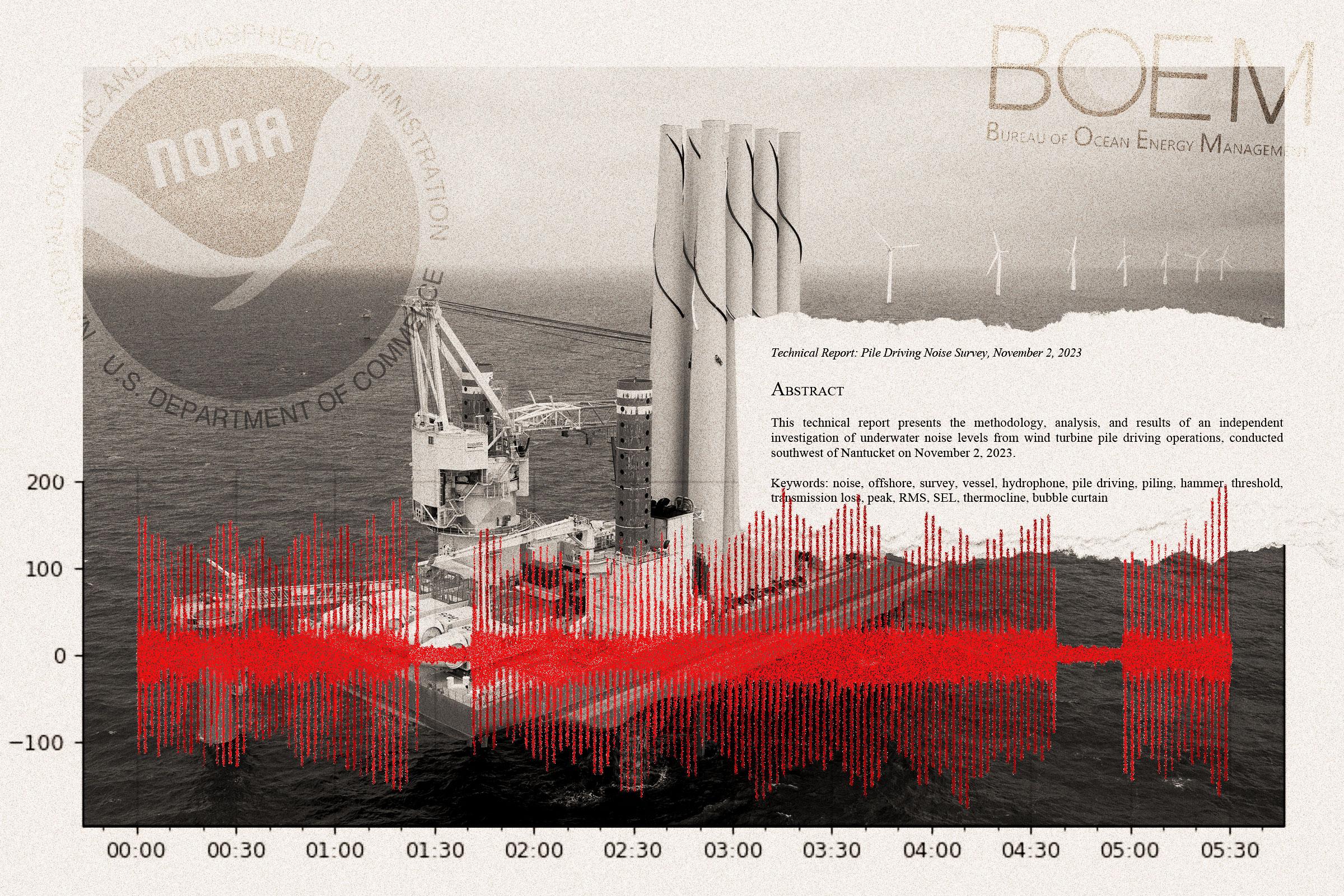

Two independent studies measuring ocean wind turbine construction noise found that the sound emitted by vessels mapping the seafloor was significantly louder than estimated and that noise protection for whales and other sea creatures during wind turbine pile driving doesn’t work.

Intense noise causes hearing loss in whales, other marine mammals, turtles, and fish, compromising their ability to navigate, avoid danger, detect predators, and find prey, according to scientific studies.

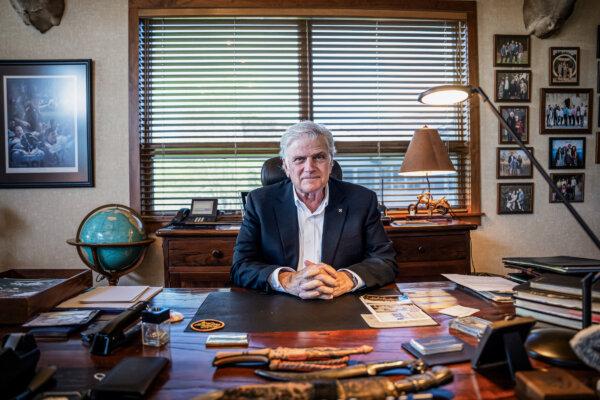

Robert Rand, an acoustics consultant with 44 years of experience, took underwater readings of the sonar survey vessel Miss Emma McCall off the coast of New Jersey. He also recorded acoustic readings of pile driving for Vineyards Wind 1, an offshore wind farm project under construction 15 miles south of Martha’s Vineyard.

The noise made by the construction vessel itself, which is not monitored, was almost as loud as the pile driving. He found that the standard formula used by the National Marine Fisheries Service to calculate how noise, over a period of time, affects a mammal’s hearing, significantly underestimates the sound levels experienced by dolphins and whales.

“These are real data,” Mr. Rand, who testified at a congressional field hearing on Jan. 20, told The Epoch Times. “I measured it. This is not a computer model. This is not a political press release. These are data.”

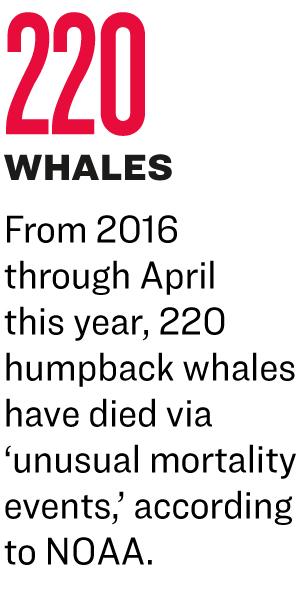

The NOAA also reported an “unusual mortality event” for North Atlantic right whales, in which 126 have died since 2017.

“The numbers have been decreasing, especially since 2017, when offshore operations really swung into gear,” Mr. Rand said.

“From my experience in noise control, that’s not a coincidence. Noise is an environmental pollutant. In human terms, it’s measured in life years lost.”

Pile-Driving Noise

On Nov. 2, 2023, Mr. Rand went out on a 29-foot sport fishing boat to the Vineyard Wind 1 construction site.The completed wind farm project will be made up of 62 wind turbines in the Atlantic Ocean, spaced one nautical mile apart. The project is estimated to provide power to more than 400,000 homes and businesses.

The offshore wind farm is owned by Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners of Denmark and Avangrid Renewables, part of the Spanish company Iberdrola.

At the construction site in November 2023, Mr. Rand said an 874-foot crane ship called the Orion was using a massive hammer to pound a monopile foundation for a wind turbine into the seabed.

The monopile is a steel pipe that is 31 feet in diameter and 279 feet long and weighs 1,895 tons, according to the manufacturer, EEW Special Pipe Constructions.

Vineyard Wind 1 implemented two sets of noise controls. The first is a “hydro sound damper,” which, according to Mr. Rand, is a vertical net in the water around the monopile that’s covered with foam or rubber blocks and balls.

The second is a “double bubble” curtain. These are two weighted hoses lying on the seafloor in concentric circles around the monopile. The radius is roughly 492 feet to 656 feet.

The hoses have holes in them, and compressed air from a support vessel is forced through the hoses, causing bubbles to rise to the surface. The bubbles are supposed to mitigate the sound pressure created by the pile driving.

“These are advanced techniques,” Mr. Rand said. “They aren’t used anywhere else.”

Unfortunately, the noise mitigation techniques don’t work, he said.

Mr. Rand dropped a research-grade, omnidirectional hydrophone into the water at six locations, starting at 4.1 nautical miles from the pile driving and moving closer to 0.57 nautical miles.

Analyzing the data, he found that even with sophisticated noise mitigation in place, the pile driving is as loud as multiple seismic air guns.

“People have been protesting and the government has been rigorously regulating seismic air gun arrays for years, if not decades, because of their sonic intensity and hazard for endangered species—for whales and other marine species,” Mr. Rand said.

“This pile driving is as loud as an array of air guns.”

The Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA) makes it illegal to kill, hunt, capture, or harass a marine mammal. Killing or injuring a mammal is considered Level A harassment under the 1972 law. Level B harassment includes actions that disrupt an animal’s normal behavior, including migration, breathing, nursing, breeding, feeding, or sheltering.

The National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) provides a guide to marine acoustic thresholds, which are considered harassment at certain levels.

“Acoustic thresholds refer to the levels of sound that, if exceeded, will likely result in temporary or permanent changes in marine mammal hearing sensitivity,” the website reads.

The NMFS noted that Level B harassment is reached when continuous noise, such as a ship engine running, hits 120 decibels or impulsive or intermittent noise, such as pile driving, hits an average of 160 decibels.

The agency says marine mammals can suffer permanent hearing loss at 173 to 219 decibels of continuous sound or 202 to 232 decibels of impulsive sound.

Based on his data, Mr. Rand estimated the pile driving noise at the source at 241 decibels. Loudness decreases as sound waves move away from the source. Still, Mr. Rand measured peak sound levels ranging from 180 decibels at a distance of 0.57 nautical miles from the ship to 162 decibels at 4.1 nautical miles.

He also found that the continuous noise of the Orion’s propulsion and positioning thrusters exceeded 120 decibels at a distance of 3.7 miles from the ship.

Why did the sound mitigation measures fail? Mr. Rand explained that sound waves travel through air, water, and land. In fact, sound travels nearly five times faster through water than air.

One likely reason why the hydro sound damper and double bubble curtain didn’t curb the noise is that they are designed to inhibit sound waves moving through water, Mr. Rand said. They have no effect on sound waves traveling through the seabed.

The formula that the NMFS uses to calculate how noise affects a mammal’s hearing is essentially 90 percent of average noise levels.

Mr. Rand used his data to perform the calculation. He found that the NMFS formula underestimated the sound level experienced by whales, dolphins, and porpoises by as much as 6 decibels.

Six decibels means four times the sound energy.

“The metric is deficient,” he said.

Offshore wind construction ships are required to have spotters watching for marine mammals during pile driving and sonar surveys. If an animal swims too close to the ship, work must stop.

But because the NMFS formula is off, the protective distance for the critically endangered North Atlantic right whale and other marine mammals is only half of what it should be, according to Mr. Rand.

“Everything looks earnest,” he said. “They’ve got the observers up on the deck. They’ve got the protective radii. They’ve got the fancy models. They’ve got all of this.

Sonar Noise

In his earlier study, published on Sept. 22, 2023, Mr. Rand measured actual noise levels generated by a sonar survey vessel. On May 8, 2023, the Miss Emma McCall was mapping the seafloor for Attentive Energy.Attentive Energy won a bid from the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management in February 2022 to lease 84,332 acres in the Atlantic Ocean located 47 miles off the coasts of New York and New Jersey.

Attentive Energy had contracts to supply power to both New Jersey and New York. Its contract for the New York project was canceled on April 19. The New Jersey contract is still in place.

The Miss Emma McCall used equipment including a multibeam echosounder, side scan sonar, and a sub-bottom profiler, or “sparker,” to reveal geological features of the seabed.

The sparker sends an acoustical pulse to the ocean floor that is reflected back to a receiver. Based on the data collected, Mr. Rand estimated the sparker source sound level at 224 decibels and peak sound levels at 151.6 decibels at one-half nautical mile away.

This was consistent with the sparker’s manufacturer specifications but louder than what the vessel stated it would generate in its permit application for incidental marine mammal harassment.

The vessel itself created continuous noise, which Mr. Rand measured at 126.5 decibels at one-half nautical mile away. But as with the pile driving ship, the permit application treated the vessel as if it were silent.

Mr. Rand reiterated that any continuous noise above 120 decibels is considered Level B harassment.

To protect marine mammals, the Miss Emma McCall was obligated to shut down the sonar survey if a North Atlantic right whale came within 500 meters (1,640 feet) of the ship, if endangered marine mammals came within 100 meters (328 feet), or if nonendangered marine mammals came within 50 meters (164 feet).

But based on Mr. Rand’s data and calculations, the sonar survey should shut down if the mammals came within one nautical mile (1.1 miles) of the ship, he said.

He said that the NMF “appears to have abandoned the evaluation of Level B behavioral harassment at 120 decibels.”

“Level A harassment due to cumulative sound exposure level appears feasible depending on time periods occupied and various distances to the sparker,” Mr. Rand wrote in his report

Federal Agency Responsibilities

The damage intense noise causes in mammals is noted in several scientific studies.Researchers from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution found that turtles exposed to excess underwater noise can experience temporary hearing loss.

The Ecological Society of America published a study showing that squid, octopus, and cuttlefish exposed to excessive low-frequency sound had severe lesions in their auditory structures, indicating “massive acoustical trauma.”

Mr. Rand said he believes that to protect marine mammals from the risk of auditory injury and behavioral harassment, federal agencies such as the NMFS, which sits within NOAA, should increase protective distances around offshore wind construction sites.

“I think NOAA should uphold the Marine Mammals Protection Act and the Endangered Species Act,” he said. “I think they strayed away from their legal requirements established by Congress.

“What I’m seeing is a relaxation of protections. And it’s very subtle because there’s so much apparent concern about the modeling and the calculations and the research on what is an appropriate level to be used for a threshold.”

The Epoch Times requested comments from the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, NOAA, and Attentive Energy. They did not respond by press time.